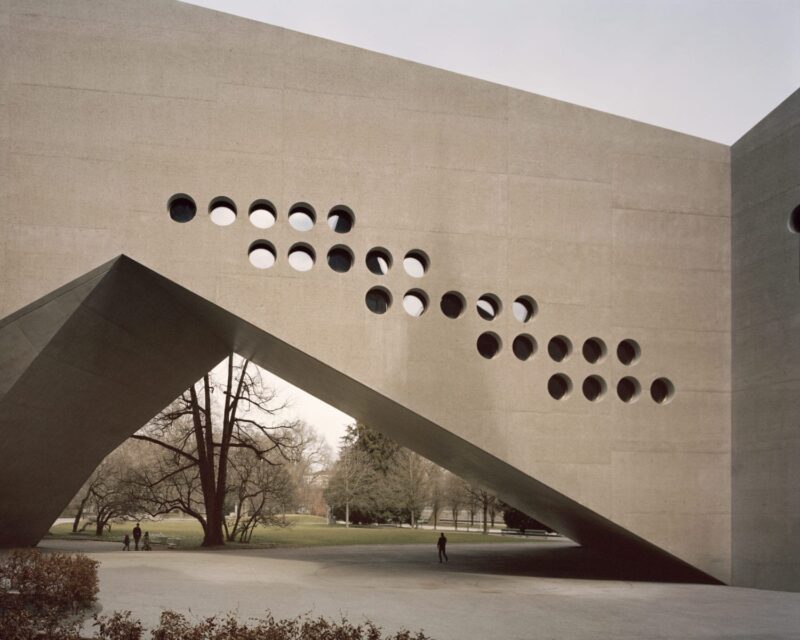

Barkow Leibinger利用两极对立之间的张力,在美学和功能上创造了非凡的建筑。他们的设计唤起了古典现代主义的灵感,同时直面未来。

Drawing on the tension between polar opposites, Barkow Leibinger creates extraordinary architecture, both aesthetically and functionally. Their designs evoke classical modernism while gazing squarely into the future.

在一排排时髦的漂亮自行车之间,矗立着一座巨大的铁结构建筑。再往上走几步,在夹层的模型制作车间里,机器还在运转,机器嗡嗡作响,捆扎、折叠、成型直接邻接在包围数字铣床的玻璃盒上,里面装着数字铣床、激光切割机等神秘的高科技工具。

Nestled between a handsome collection of hipster bicycles stands a colossal iron structure.A few steps up, in the model building shop on the mezzanine floor, the operation is still up and running—machines hum along, bundling, folding, and forming directly adjacent to a glass box encasing a digital milling machine, laser cutters, and other mysterious high-tech tools.

采访档案 |Barkow Leibinger 德国柏林 | 建筑师

在楼上明亮通风的阁楼里,一群人坐在电脑前。在Jac Jacobsen设计的经典挪威Luxo灯具的照射下,整个房间沉浸在一片静谧之中。正是在这里,Barkow Leibinger开辟了创造他们作品的空间。

A scattering of people are seated at computers in the bright airy lofts above. A concentrated silence permeates the rooms, bathed in light cast by the classic Norwegian Luxo lamps designed by Jac Jacobsen. It is here that Barkow Leibinger have opened a space in which to create their work.

“我们的工作流程是做事和思考的辩证法。”Frank Barkow解释道,“来来回回,你可以将这个过程智能化,当然这个概念很重要,但从本质上讲,它是关于材料的。它是关于尝试新旧工具以及表单本身。这个概念随项目而来,但最终都回归到设计中。”这种持续不断的辩证法,其根源在于该公司创始人之间的顽皮对立的力量,他们之间的差异大得不能再大了。比如来自蒙大拿腹地的Frank Barkow,他是一位“砖匠”,也是一位有着一千个想法的修补匠,在活跃的对话中,他的手指会飞到桌子上方,就好像在寻找钢琴键、蜡笔或锤子。还有Regine Leibinger,她是一位商业大亨的女儿和一位艺术品交易商孙女,接受过古典教育,在这一过程中学会了斯瓦比亚式的经商技巧。

“Our work flow is a dialectic of doing and thinking. A constant back and forth,” explains Frank Barkow. “You can intellectualize the process, of course the concept is important, but at its core, it’s about the material. It’s about experimenting with old and new tools and with the form itself. The concept comes with the project, but it all comes back around to the design.” This ongoing dialectic has its origins in the playfully opposing forces of of the company’s founders, who couldn’t be more different. There’s Frank Barkow from deep Montana, a “Bricoleur” and tinkerer with a thousand and one ideas, whose fingers fly over the table top during animated conversation, as if in search of piano keys, a crayon or a hammer. And then there’s Regine Leibinger, the bubbly business magnate’s daughter and granddaughter of an art dealer, who was given a classical education and acquired a Swabian knack for business along the way.

B-L Schaufenster是Barkow Leibinger的画廊空间。

B-L Schaufenster是Barkow Leibinger的画廊空间。

不太可能的一对。然而,当这两个人在90年代早期第一次在哈佛大学见到时,就一见钟情了。“这真的很有趣,”Barkow回忆道,“Regine非常理性,非常欧洲化——非常老练。我更有实验精神和表现力。但我们对空间和材料都很敏感。”“是的,”Leibinger附和道,“我们都是从空间布局的角度来考虑的。建筑立面,天花板,屋顶,第五立面。我们对材料有着同样疯狂的兴趣。我的总是具体的,对弗兰克来说,基本上什么都是。但是我们当时的观点完全不同。”

An unlikely pair. And yet, it was love at first sight when the two first met at Harvard University in the early ’90s. “It was really funny,” recalls Barkow. “Regine was very rational, very European—so sophisticated. I was more experimental and expressive. But we shared a sensitivity to space and materials,” he adds. “True,” Leibinger chimes in. “We both always thought in terms of spatial layouts. And about building facades, ceilings, roofs, the fifth facade. And we shared this insane interest in materials. Mine was always concrete and for Frank, oh, basically everything. But our perspectives at that time were totally different from one another.”

这也就不足为奇了。毕竟,Berlin刚刚走出柏林,后现代主义在80年代早期风靡一时。学生们都在学习密斯·凡德罗(Mies van der Rohe)和布鲁诺·陶特(Bruno Taut)等人的住宅建筑。当时的国际建筑展览涉及“批判性重建”和约瑟夫·保罗·克莱休斯(Josef Paul Kleihues),这让Berlin重新认识了彼得·艾森曼(Peter Eisenman)和路易·卡恩(Louis Kahn)等美国建筑师。

And it’s no wonder. After all, Leibinger was fresh out of Berlin, where postmodernism was all the rage in the early ’80s. Students were learning about residential architecture from the likes of Mies van der Rohe and Bruno Taut. The International Architecture exhibition at that time dealt with “critical reconstruction” and Josef Paul Kleihues, which opened Leibinger’s eyes to American architects like Peter Eisenman and Louis Kahn.

这些是Frank Barkow在入读哈佛大学之前没有听到过的名字。“我从不知名的地方来到这里。蒙大拿州与建筑语言相去甚远,所以我认识的第一批建筑师是巴克明斯特·富勒(Buckminster Fuller)和安特农场(AntFarm)。或者布鲁斯·戈夫(Bruce Goff)和他的偶像弗兰克·劳埃德·赖特。”在蒙大拿州广袤的土地上,巴克成长于以农业和重工业为特征的建筑之中——铁路、水坝、采矿和木材。“基础设施不仅仅是建筑,真的。到目前为止,景观和建筑之间的这种联系对我来说仍然非常重要,”Barkow说,“蒙大拿州的这些小山城拥有19世纪淘金热时期建造的美丽建筑典范。这也是为什么我爱上了艺术家唐纳德·贾德(Donald Judd),他说,美国最美的东西都是由工业塑造的。”

These were names which Frank Barkow hadn’t heard much about before enrolling at Harvard. “I came literally from the middle of nowhere. Montana was pretty far removed from architectural discourse, so the first architects I knew were Buckminster Fuller and AntFarm. Or Bruce Goff and his idol Frank Lloyd Wright.” In the vast lands of Montana, Barkow grew up with architecture that was marked by agriculture and heavy industry—railroads, dam buildings, mining, timber. Infrastructure more than architecture, really. “This connection between landscape and building is still very important to me to this day,” says Barkow. “These small mountain towns in Montana have beautiful examples of architecture that were created during the gold rush of the 19th century. That’s also why I came to love the artist Donald Judd, who said, the most beautiful things in the USA were shaped by industry.”

高中毕业后,这位十七岁的孩子开始用简单的工具建造木屋。 正如他的妻子Regine所说,他对建筑有了直观的“本土理解”。但最终是美国人的自我决定,一种为自己思考和做事的态度,促使他学习建筑。“从一开始,我就很得心应手,我有自己动手盖房子的技能。但是Regine所用的所有知识和参考资料都很有趣,我必须一步一步地慢慢地学习。”

After finishing high school, the seventeen-year-old started building wooden houses with simple tools. He developed an intuitive “native understanding” of architecture, as his wife Regine puts it. But ultimately it was American self-determination, the attitude of thinking and doing for yourself, which led him to study architecture. “From early on I was pretty handy, and I had the manual skills to build houses on my own. But all the knowledge and references that Regine used so playfully, I had to learn the hard way, slowly, step by step.”

模型制作车间是Barkow Leibinger的设计师动手的地方。他们利用激光切割机和3d打印机等新兴技术,将新的建筑理念打造成定制的微缩模型,让每个人都能触摸到。

模型制作车间是Barkow Leibinger的设计师动手的地方。他们利用激光切割机和3d打印机等新兴技术,将新的建筑理念打造成定制的微缩模型,让每个人都能触摸到。

然而,正是由于他们截然不同的方法,Barkow Leibinger的作品才如此特别。在比赛取得初步成功之后,美国的经济衰退以及斯图加特的狭隘思想将他们引向了后柏林墙时代的柏林,当时的柏林正随着社会变革、艺术、音乐和摄影而飞速发展。他们的第一间办公室位于Regine在Schöneberg的旧工作室公寓内。1998年,他们在斯图加特附近的迪津根建造了屡获殊荣的Trumpf工厂,从而取得了突破性进展。

And yet it is due to their disparate approaches that the work of Barkow Leibinger is so special. After some initial success at competitions, the recession in the US and and the narrow mindedness of Stuttgart pointed them in the direction of newly post-wall Berlin, which was pulsating with social change, art, music, and photography. Their first office was situated in Regine’s old studio apartment in Schöneberg. Their breakthrough followed soon after in 1998 with the award-winning Trumpf laser factory in Ditzingen, close to Stuttgart.

当Frank Barkow与Regine的父亲Berthold坐在一张桌子旁时,两人之间不可否认地擦出了火花。Berthold是一位真正的修补匠和艺术爱好者。“Berthold是一位德国天才,”Barkow盛赞道,“他像工程师和诗人一样思考。他给了我们自由,但也给了我们适当的反击,只有通过Trumpf,我们才找到了通往金属的道路。”

When Frank Barkow sat down at a table with Regine’s father Berthold, a true tinkerer and art lover, there were undeniable sparks between the two. “Berthold is a German genius,” Barkow raves. “He thinks like an engineer and a poet at the same time. He gave us freedom but also the right amount of push back, and it was only through Trumpf that we found our way to metal.”

这个故事多少让人想起沃尔特•格罗皮乌斯(Walter Gropius),他为卡尔•本谢德(Carl Benscheidt)在阿尔菲尔德建造了如今著名的法格斯工厂。它是所谓的Fagus-knot,两个交叉的横梁,允许Gropius使用钢框建造落地窗,而不使用可见的结构支撑,从而产生开放感。Barkow Leibinger在很大程度上要归功于他们与著名工程师Werner Sobek的合作,如果没有他,他们就不会创造出Trumpf食堂巨大的屋顶结构,食堂坐落在几根细丝钢柱上。屋顶上的多边形、部分上了釉的木质蜂巢不仅是家居装饰,它们还能吸收食堂里一些噪音很大的咔嗒声和喋喋不休的声音。下面的空间可以很容易地变成画廊、礼堂或圣诞派对的场地。“但是,当然,你也可以在那里吃Maultaschen,这是非常重要的。”Barkow补充说。

This story is somewhat reminiscent of Walter Gropius, who built the now famous Fagus Factory in Alfeld for Carl Benscheidt. It was the so-called Fagus-knot, two crossed beams, which allowed Gropius to construct floor to ceiling windows using steel frames without the use of visible structural support, resulting in a sense of openness. Barkow Leibinger owe a great deal to their collaboration with the renowned engineer Werner Sobek, without whom they wouldn’t have created the massive roof construction of the Trumpf Canteen, which rests on a few filigree steel columns. The polygonal, partially glazed wooden honeycombs that populate the roof are not just homely ornaments, they also absorb some of the the noisey clatter and chatter of the canteen. The space below can easily transform into a gallery, an auditorium or a venue for a Christmas party. “But, of course, you can also eat Maultaschen there, which is very important,” adds Barkow.

在技术和材料以及生产方法上的创新,似乎丰富了Barkow Leibinger的艺术创造力。Albert Kahn在底特律的福特工厂标志着“福特主义”的开始,这不仅改变了工业生产,也改变了整个社会。Regine Leibinger解释说:“这是我们第一个使用工业4.0原理建造的建筑。”的确,俯瞰控制室中的巨型显示器机房,配有弯板机和激光切割台,这些让人想起史蒂文•斯皮尔伯格(Steven Spielberg)《少数派报告》(Minority Report)中的科幻幻想。

Innovations in technology and materials as well as production methods seem to fertilize the artistic creativity of Barkow Leibinger’s designs. Albert Kahn’s Ford factory in Detroit marked the beginning of “Fordism”, which not only changed industrial production, but also society as a whole. In the not-so-distant future, one might look back and see Barkow Leibinger’s Smart Factory for Trumpf in Chicago as a pioneering piece of industrial construction. “It’s our first building created using the principles of Industry 4.0—the digitized, globally linked production network utilizing artificial intelligence,” explains Regine Leibinger. Indeed, the giant displays in the control rooms overlooking the machine rooms with the plate bending machines and the laser cutting stations are reminiscent of the science fiction visions in Steven Spielberg’s Minority Report.

步入式档案馆,获奖设计的微缩模型放在与学生一起完成的投机性研究模型旁边。

步入式档案馆,获奖设计的微缩模型放在与学生一起完成的投机性研究模型旁边。

为了抵消高科技设备的丰富,通风的门厅覆盖着温暖的松木,立面小心翼翼地生锈。毕竟,芝加哥位于美国“铁锈地带”的边缘,而“铁锈地带”是美国汽车工业的心脏地带,如今已不复存在。Barkow解释说:“在某种程度上,这个建筑已经过时了,但是仍然在不断进步。”“我们结合了美国工业历史的材料和美学——钢铁、密斯·凡德罗(Mies van der Rohe),以及美国高速公路的建设——唐纳德·贾德(Donald Judd)认为,高速公路上的桥梁和标志对美国文化产生了重大影响——并将它们与工业4.0的高科技新工艺相结合。”这就是我对它如此感兴趣的原因。”

To counteract the abundance of high-tech gear, the airy entrance hall is covered with warm pine wood and the facade is left discreetly rusted. Chicago is, after all, at the edge of the American rust belt, the now defunct heart of the old American automobile industry. “The architecture is archaic on some level while still managing to be progressive,” explains Barkow. “We tie in the materials and the aesthetic of American industrial history—steel, Mies van der Rohe, and the construction of the American freeway, whose bridges and signs, according to Donald Judd, are a major influence on American culture—and combine them with the new high-tech processes of industry 4.0. That’s what makes it so interesting for me.”

Barkow Leibinger将传统、工艺、数字化和审美精准结合在一起,形成了具有清晰功能的空间设计艺术概念,这种独特的方式可以在他们位于柏林的美国学院展馆中看到。玻璃屋为学院的学者们提供了令人愉快的简单工作空间,可以俯瞰位于德国首都西南方向的大旺西湖。它让人想起密斯·凡德罗的范斯沃斯住宅的当代变体,但屋顶结构复杂,采用了钢结构。这个想法源自一位摩洛哥织布工,他向Barkow Leibinger展示了自己有数百年历史的手艺,然后把它带到柏林,在那里,研究小组对地毯进行了数字化、缩放,并把地毯的质地变成了一个巨大的装置,由1001根松木悬挂的棉线组成,用于马拉喀什双年展(Marrakech Biennale)。这个双曲线结构的元素现在高耸于 Greater Wannsee顶上。

The particular way in which Barkow Leibinger weaves together tradition, craftsmanship, digitization and aesthetic precision into an artistic concept of spatial design with clear functionality can be seen in their pavilion for the American Academy in Berlin. The glass bungalow offers the scholars of the academy delightfully simple workspaces overlooking Greater Wannsee, a lake located in the south west of the German capital. It evokes a contemporary variation of Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House, but with a complicated, offset roof structure made of steel. The idea for this was born from a Moroccan weaver, who showed Barkow Leibinger his centuries-old craft, which was then taken to Berlin where the team digitized, scaled, and transformed the texture of the carpets into a gigantic installation made of 1,001 pine-suspended cotton threads for the Marrakech Biennale. Elements of this hyperbolic structure are now towering over the heads of the fellows at Greater Wannsee.

Frank Barkow说:“我们也将我们的办公室视为一个研究平台。”“当我们看到一个问题的潜力时,我们会把它带给哈佛和普林斯顿的学生,在那里我们可以以极高的水平来解决它。“这正是Chris Bangle为宝马公司设计的一款乌托邦式的汽车如何转变为灵活、可持续的经济适用房结构。就像在他自己的办公室里一样,正是这种动态的紧张关系,一种以眼睛的高度看待事物的方式,对最佳解决方案的怀疑和挣扎,让Barkow对哈佛“艰苦的教育”心存感激:“我需要这种抵抗,”他坚持说。“这些年轻的、充满干劲的学生向我挑战,”Leibinger证实道。“当涉及到新技术、新材料和新视角时,他们也让我跟上时代。”

“We also see our office as a research platform”, says Frank Barkow. “When we see potential in a problem, we take it to our students at Harvard and Princeton where we can work on it on at an extremely high level.” This is exactly how a utopian car design that Chris Bangle made for BMW turned into flexible, sustainable structures for affordable housing. Like in his own office, it is this dynamic tension, a way of approaching things at eye level, the doubts and the struggle for the best solution, that Barkow appreciates about the “tough schooling” of Harvard: “I need this resistance,” he insists. “These young, very motivated students challenge me,” confirms Leibinger. “They also keep me up to date when it comes to new technologies, materials, and perspectives.” The best ones tend to join their office in Berlin, a city whose creative energy the two swear is second to none.

在从他们选择的城市中汲取无限灵感的同时,Barkow Leibinger用他们自己的建筑慢慢塑造柏林的城市景观。像是2012年中央火车站(火车总站)总体规划项目的旅游总部大楼,或Neukölln的Estrel塔,它将成为该市最高的建筑。建筑师们甚至在推动传统的保守开发商,比如柏林的一家房屋建筑公司,将创新方法融入到他们的建筑实验中。“这种由柏林理工大学土木工程师Mike Schlaich开发的新型建筑材料令人惊叹:它不仅支持和保护材料免受磨损,而且还提供绝缘材料,并且完全可回收利用。我们是第一次用这种材料建造高层建筑。” Leibinger解释道。

While drawing infinite inspiration from the city of their choice, Barkow Leibinger slowly shape Berlin’s urban landscape with their own buildings. Just take a look at the elegantly twisted Total skyscraper at the main train station from 2012, or the Estrel Tower in Neukölln, which is slated to be the tallest building in the city. The architects are even moving traditional conservative developers like a Berlin housing construction company to integrate innovative methods into their building experiments. “This new building material developed by civil engineer Mike Schlaich at the TU Berlin is amazing: it not only supports and protects the material from wear and tear, it also provides insulation and is fully recyclable. We are making a highrise out of the material for the first time,” explains Leibinger.

几年前,Barkow Leibinger实现了他们在纽约拥有一间办公室的老梦想。“我对美国建筑非常不满,”Barkow说。“我认为我对建筑的欧洲化理解可以帮助它变得更好。”按照勒柯布西耶(Le Corbusier)、埃里希门德尔松(Erich Mendelsohn)和其他流亡建筑师的传统,他们在20世纪二三十年代帮助塑造了美国的建筑文化,来自蒙大拿州深处的美国建筑师弗兰克·巴科(Frank Barkow)回到祖父的土地上,将教育,艺术感和建筑文化带回美国。即使纽约办公室还处于起步阶段,Barkow也喜欢这种说法。 这是理论上不太可能但实际上卓有成效的组合之间的又一个桥梁:Barkow和Leibinger。

A couple of years ago, Barkow Leibinger made their old dream of having an office in New York come true. “I’m pretty critical of American architecture,” says Barkow. “And I think my Europeanized understanding of architecture can help to make it better.” In the tradition of Le Corbusier, Erich Mendelsohn and other exiled architects who helped to shape American building culture in the 1920s and ’30s, Frank Barkow, an American architect from the depths of Montana, returns to the land of his grandfathers to import education, a sense of art and architectural culture back into the USA. Even if the New York office is still in its infancy, Barkow enjoys this narrative. It is yet another bridge between this theoretically unlikely but practically fruitful combination: Barkow and Leibinger.

本文是《建筑师对话》系列的一部分,由Freunde von Freunden和西门子家用电器公司共同制作,他们采访了四位获奖建筑师和室内设计师来探讨当代设计理念、城市生活趋势和全球挑战。

This story is part of Architect Dialogues, an interview series by Freunde von Freunden and Siemens Home Appliances that explores current design philosophies, urban living trends, and global challenges with four award-winning architects and interior designers.

版权归属

Text © Sarah Elsing for FvF Productions

Photos © Daniel Gebhart de Koekkoek for FvF Productions